Building Return on Investment from Cloud Computing – Introduction

Cloud Computing has been described as a technological change brought about by the convergence of a number of new and existing technologies.

The promise of Cloud Computing is primarily the following key technical characteristics (see Above the Clouds [4]):

- The ability to create the illusion of infinite capacity; the performance is the same if scaled for one, to a hundred, or a thousand users with consistent service-level characteristics.

- Abstraction of the infrastructure so applications are not locked into devices or locations.

- Pay-as-you-go usage of the IT service; you only pay for what you use and with no or minimal up-front investment costs. You typically just use the service through a connection and device.

- The service is on-demand; able to scale up and scale down with near instant availability. Typically, no forward planning forecast is required.

- Access to applications and information from any access point.

But this is only half the story. These technical characteristics can also be found in non-disruptive technology solutions. The rate of change and magnitude of cost reduction and specific technical performance impact of Cloud Computing are not just incremental, but can give a five to ten times order of magnitude improvement.

The Capacity-Utilization Curve

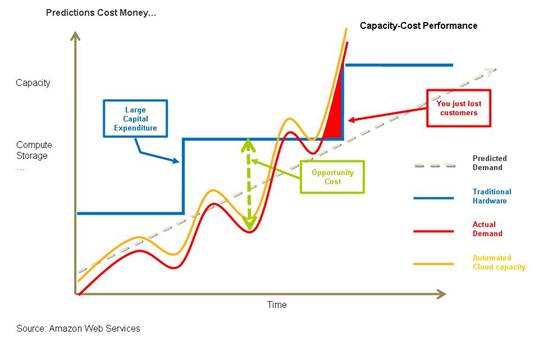

The famous graph used by Amazon Web Services illustrating the capacity versus utilization curve has become an icon in Cloud Computing. The model illustrates the central idea around Cloud-based services enabled through an on-demand business provisioning model to meet actual usage.

The Capacity versus Utilization Curve

Why this matters to business is that one of the core precepts of Cloud Computing is to avoid the cost impact of over-provisioning and under-provisioning. This is in addition to the opportunity for cost, revenue, and margin advantages of business services enabled by rapid deployment of Cloud services with low entry cost, and the potential to enter and exploit new markets.

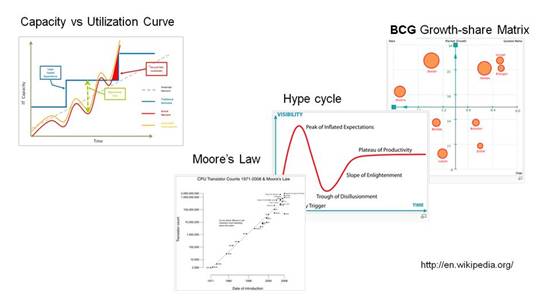

We contend that in years from now, when Cloud Computing is seen in a historical context, the capacity versus utilization curve will be seen as an iconic model that had the same effect as previous well known business models.

Iconic Business Models

Examples of these include:

- The Moore’s Law model that establishes the concept of exponential growth in computational power but has subsequently been seen in other technology areas, including storage and network

- The technology hype cycle that established the emergence of innovation lifecycles, and is developed in publications by Charles H. Fine [2] and Clayton M. Christensen [3]

- The Boston Consulting Group Growth-Share Matrix that can be used to show how key industrial markets and products and services undergo transitions as the maturity lifecycles emerge, grow, and recede

But what does this potential icon mean for business? Matching capacity and actual utilization on demand improves operational efficiency, but is that all there is to it? Capacity and utilization are Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). They measure how much or how little something is being used. But is this aligned and being used to generate Return on Investment (ROI)?

Race to the Bottom versus Quality of Service (QoS)

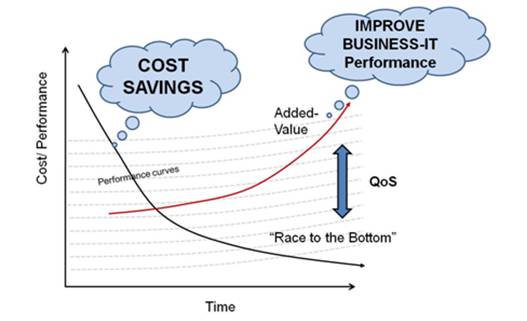

The positioning of Cloud Computing, while initially seen as a disruptive technology influence on both buyer and seller prospects, is now evolving into a trade-off between low-cost arbitrage and added value Quality of Service (QoS).

Race to the Bottom

The terms “race to the bottom” or similarly the “prisoner’s dilemma” refer to the competing drive between participants in a market driven by the need to make the greatest cost savings. The term is often seen in a negative context, as the lower costs and margins are seen as a detriment to the participants. Massively scalable services from Cloud Computing providers have the effect of driving down costs and prices, as the dynamics of competition are shifted by the presence of potentially rapid cost reductions and huge data center investments.

The counter-balance to this is the Quality of Service (QoS), and the associated Cost of that Service (CoS) that characterizes the value of the cost per unit of performance provisioned (see the discussion on the Financial Value Perspective of Moving from CAPEX to OPEX and Pay-as-you-go).

The differentiator of Cloud Computing is not just the utility infrastructure computing services, but includes all the higher-level services that enhance and build business service value. We see this as the influence and scope of the movement from IT-centric to business-centric services across a wider services continuum, with utility services for infrastructure at one end, and with business-centric software and business processes delivered as a service from the Cloud at the other.

In addition, the need to provide adequate security should be considered. People are willing to pay a little more for a service if they are assured that there will be good security measures in placed.

This issue is highlighted in this White Paper as it has a direct bearing on the Cloud Computing ROI debate and how it is measured:

- Pricing and costing of Cloud services

- Funding approaches to Cloud services

- Return on Investment (ROI)

- Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

- Total cost of ownership (TCO)

- Risk management

- Decisions and choices evaluation processes for Cloud services

The discussion of the market dynamics of Cloud Computing is not developed further in this White Paper, but is a recommended area of research going forward as more products and services become Cloud-enabled.

Traditional IT Compared to Cloud Computing

The iconic capacity versus utilization curve of Figure 1 provides a yardstick of current thinking in Cloud Computing provisioning. It is shown here for increasing demand, but the same model can be applied to both growth and decline of capacity demand in a periodic pattern typical of many businesses.

The following table shows some of the characteristics of traditional IT compared to Cloud-Computing.

Traditional IT |

Cloud Computing |

|

|

New Technology Adoption Lessons from Other Industries

Understanding the characteristics of Cloud Computing can be assisted by observations from other industries that are in the process of transformation. Lessons from alternative power sources such as solar energy and wind power contain examples of issues that resonate with familiarity in the Cloud Computing context.

When comparing Cloud Computing to solar and wind energy there are similar adoption issues:

- Potential unlimited energy resource

- Challenges to distributing efficiently

- Demonstrating its value over traditional/other alternatives

Solar Energy and Wind Power

Just taking a look at the solar energy and wind power characteristics:

- Global current human demand in 2009 is 16 terawatts; this is predicted to rise to 20 terawatts by 2020 (refer to Wikipedia: World Energy Resources and Consumption).

- Sunshine on earth area 120,000 terawatts (174 petawatts – 30% reflected back); that is, 60,000 times more than demand (refer to Wikipedia: Solar Energy).

- 100 square miles of solar farms with today’s technology could collect enough power for the whole of the USA (refer to US Department of Energy on solar energy).

- Germany is a leader in solar power – a country with average to poor locality for sunshine but demonstrating leadership (refer to Wikipedia: Solar Energy).

- 10/15 solar farms can generate 1.3 Gigwatts = medium size coal power station (refer to Wikipedia: Solar Farm).

- California law states 20% power from renewables by 2010 (refer to the California Energy Commission on renewable energy programs).

- President Barack Obama Federal Renewables Policy requires 25% from renewables by 2025 (refer to the US Environmental Policy).

- 25% of UK electrical power could be sourced from 6000 220m tall wind turbines positioned 100 miles off-shore in the North Sea (refer to the UK Government Carbon Trust).

New Technology Adoption from a Buyer’s and Seller’s Perspective

Examining the issues of effective wind power or solar energy compared to contemporary energy sources draws parallels with the challenges we also see in defining new technology adoption.

Sellers of resources and services characteristically focus on their operation and technical development, and how they can enable effective business models for existing and potential new customers and markets.

Buyers are typically not concerned about how the sources of energy, resources, or services were generated and delivered. They seek to understand whether their businesses can be supported by the products or services, and whether these can be reliable and cost-effective. Buyers want to know the choices on offer and how they may be able to enhance or swap resources and services for improved business performance.

The following table shows some of the concerns of buyers and sellers of new technology.

Buyers |

Sellers |

|

|

In Cloud Computing the common themes in engaging sellers and buyers in the new technology provisioning model includes three key questions:

- How does Cloud Computing compare to traditional IT? This principally relates to the comparison of service-level performance and license costs.

- What can I not put in the Cloud? Answers typically include UNIX systems, mainframes, and very high I/O applications, but pretty much anything can be co-located or hosted in an elastic virtual container environment. Beyond the technical definitions there are the business processes and provisioning models that set Cloud Computing apart from its predecessors of utility computing and virtualization.

- How does Cloud Computing impact revenue and budget lines? This issue involves the cost/performance enabled by virtualization and economies of scale, and the lowered need for up-front investment. Movement of revenue to Cloud providers may need to be balanced by sale of added-value services.

Above and Beyond the Clouds

There are many definitions and viewpoints provided by the sellers of what is now termed “Cloud Computing”. Much of the vocabulary used is defined from the perspective of IT performance and capacity, and the impact of cost savings of asset ownership and variable seller service costs. Yet all these have direct cost-benefit impact on the business consumers of the end services and how they compete and deliver products and services in their industry.

Many business IT departments have addressed emerging trends through actions to drive cost reduction and leverage IT service providers’ adoption of Cloud style services. Many industry organizations and leading IT suppliers of software, hardware, and services, seeking to address their customer needs, have vigorously evaluated and followed a Cloud-style strategy. The challenges and issues are in the transition from the current traditional IT to the new potential capabilities of Cloud Computing. They must be expressed in a language that business end users can understand, and relate to investment, cost improvements, or business performance.

Closer to home in understanding the issues of Cloud Computing, we can draw upon the University of California, Berkeley RAD Lab. White Paper Above the Clouds [4]. This highly informative paper identifies the technical issues for Cloud adoption, and its potential for business benefits and technical challenges. The paper also sheds light on the value that these technical scenarios can provide to business:

- Avoid missed business opportunities from under-provisioning and over-provisioning (Page 1)

- Responsive Service to variable demand (Page 2)

- Pursue emergent and explorative new business market opportunities hitherto unforecast or predicted (Page 2)

- Perform cost associative tasks fast and lower cost (Page 2)

- Decouple utility services and brokering from business front end (the “fab-less” chip foundries example) (Page 3)

- Make more money from amortizing economies of scale (Page 4)

- Leverage existing investments through hybrid means (Page 4)

- “Anywhere” services, “border-less” delivery (Page 4)

This interpretation of the Above the Clouds White Paper in a business-issue context illustrates some interesting aspects of Cloud Computing potential.

The decoupling of resources and provisioning (what can be termed “back end”) from the “front end” business use through intermediation follows much the same argument as Why Buy the Cow [5] from Ivar Subrah on how on-demand powers the economy and The Big Switch [6] by Nicolas Carr that takes the analogy even further with distributed industrial IT services.

The business of IT becomes that of leveraging the products and services through competing platforms and channels to defend, attack, and build customers and market share (see the discussion on the Importance of a Business Perspective of the Cloud).

However, a secondary issue from this, described as a “race to the bottom” by many industry observers, arises where commodity charging lowers the cost, removing margin benefits. The counter-balance to this is the Cost of Service (CoS) and Quality of Service (QoS) charges and added value on top of the products and services. We explore this in the next section.

Even after the passing of time from the date of publication of Above the Clouds [4], the technical challenges are still evident, but they are becoming less so with the evolution Cloud services and technology.

The Above the Clouds paper famously asserts that Private Cloud is not Cloud Computing (Page1) as it is not open to the general public, which is part of the original definition. This illustrates that definitions of Cloud are still evolving, and perhaps the definition commonly assumed in the marketplace today does not necessarily require openness, though it still retains the central concepts of elastic capacity and provisioning.